ARTICLE AD BOX

On a cloudy November day on the west side of St. Paul, Camila Valenzuela-Panza pulls up to Alex McDougall and her husband and Josh’s home. She puts on her mask, knocks on the door and is greeted by two-week-old Diindiisi in McDougall’s arms.

The night before Diindiisi cried for three hours straight. Valenzuela-Panza, the only international board certified lactation consultant in Minnesota that does free at home-visits to her knowledge, asks McDougall to walk her through the last 24 hours. Diindiisi was cluster feeding, a type of breastfeeding where babies eat more in shorter periods of time.

“I want you to dig a little deeper and be gentle with yourself,” Valenzuela-Panza said, who was born in Chile and whose ancestors are the Mapuche people of the south of Chile and Argentina.

“Because he skipped longer periods, he was making up for it. Babies are so smart. They’re like ‘alright, Mom, I’m going to let you rest, but in a day I’m going to make up for it and I’m going to clusterfeed.’ Clusterfeeding is just a new way of getting to know your baby and it sucks. It can be really tiring, right?”

Valenzuela-Panza continues her visit with McDougall for the next hour going over breastfeeding tips, how to safely co-sleep and when to introduce pumping breastmilk. Like some of her other clients, McDougall met Valenzuela-Panza in her class she teaches at the Ain Dah Yung Center. Later when McDougall gave birth to Diindiisi, she went through something Valenzuela-Panza says is common for Indigenous parents and parents of color — she wasn’t being listened to.

While her delivery process went smoothly and she had an attentive midwife, things changed when she reached the recovery space. She was told she may not be able to breastfeed, and when she noticed Diindiisi had a tongue-tie, providers dismissed her. She knew she had to call Valenzuela-Panza.

“I tracked her down and it was so helpful because it is scary,” McDougall said. “I just really wanted to feed my baby and it was a rough first 24 hours, it was so painful and then it was immediately fixed.”

Valenzuela-Panza got to the hospital shortly after McDougall’s call. She validated McDougall’s suspicion of the tongue-tie and was able to help connect her to treatment. McDougall’s situation and the care Valenzuela-Panza was able to provide is unique — it can be hard to get direct, immediate care.

“There are not a lot of outpatient lactation consultants and even the ones that are, you see them weeks later,” Valenzuela-Panza said, who also works at the Division of Indian Work. “Sometimes they can fit you in, but not really. And most of the lactation consultants don’t take insurance because insurance doesn’t pay the hospital very much because consultants are not considered a very valuable care.”

Reclaiming breastfeeding as a cultural practice

The Indigenous Breastfeeding Coalition of Minnesota is a growing movement to support Indigenous people in their breastfeeding journey no matter what the prevailing trends may be in larger society. The group of educators like lactation consultants and doulas help promote the importance and normalization of milk medicine.

Valenzuela-Panza is part of the coalition, and Shashana Skippingday and Pearl Walker-Swaney are co-leaders. Skippingday is the director of programs at the Division of Indian Work and the founder of Nitamising Gimashkikinaan, a perinatal and lactation support nonprofit. Walker-Swaney is a doula and lactation counselor for Mewinzha Ondaadiziike Wiigaming in Bemidji.

Skippingday, a member of the White Earth Nation, knew from a young age she wanted to breastfeed when she had children but she was not yet aware how much the practice would steer her future.

Her journey in the field has led her to many different jobs including a registered nurse, lactation counselor, certified nursing assistant, medical case manager, doula, family spirit infant parent specialist and now, she’s studying to be a midwife.

For Skippingday and many other Indigenous people who work in the field, it is key they say for new parents to have access to doulas, midwives and lactation consultants that look like them. Breastfeeding practices can be culturally different, and the extra care that can be provided through representation can empower new parents.

“I totally think we all need to come together and stand up and say ‘here we are, we’re part of the community too’ and we need to be a part of the work that is being done. Don’t forget us. We’re here. We’re still here,” she said.

According to the Minnesota Department of Health, breastfeeding rates are some of the lowest in the state among the Indigenous community. This can be caused by many factors including lack of support, decreased access to prenatal education and a past history of sexual violence.

Federal data reports that 84 percent of Native women have experienced gender-based violence, and over half have experienced sexual violence.

Valenzuela-Panza says she can immediately tell when working with clients if they have experienced sexual violence. Breastfeeding can be harder, and Valenzuela-Panza will often teach survivors differently.

“It can actually give you the sensation of hate when you breastfeed when you have been sexually assaulted and you don’t want to give that to your baby so you end up teaching it very differently,” she said.

While many families are interested in breastfeeding, McDougall says it isn’t always an easy experience.

“There’s all these different things that tie into it and make it [breastfeeding] harder to reclaim. We can talk about needing to reclaim Indigenous values, but there’s also a lot of shame that comes with it if you don’t want to or can’t.”

‘There has to be something better’

In Bemidji, Walker-Swaney was inspired to get more involved supporting Indigenous breastfeeding for the same reasons as Skippingday and Valenzuela-Panza — they simply want to make things better for the next generation.

Walker-Swaney, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and affiliated with White Earth Nation, says when she started breastfeeding after her first child, she didn’t have the type of support she has been able to provide to families.

“I wanted to quit so many times,” she said. “And that is kind of what inspired me to be like, what am I missing? What can I learn about this process? Because there has to be something out there. There has to be something better.”

Much of her teaching focuses on reintroducing breastfeeding as an ancestral practice. She says she views herself as informing people, but never pressuring them. That was the case at the Indigenous Breastfeeding Gathering this fall, an annual event that educates the community about resources available to them.

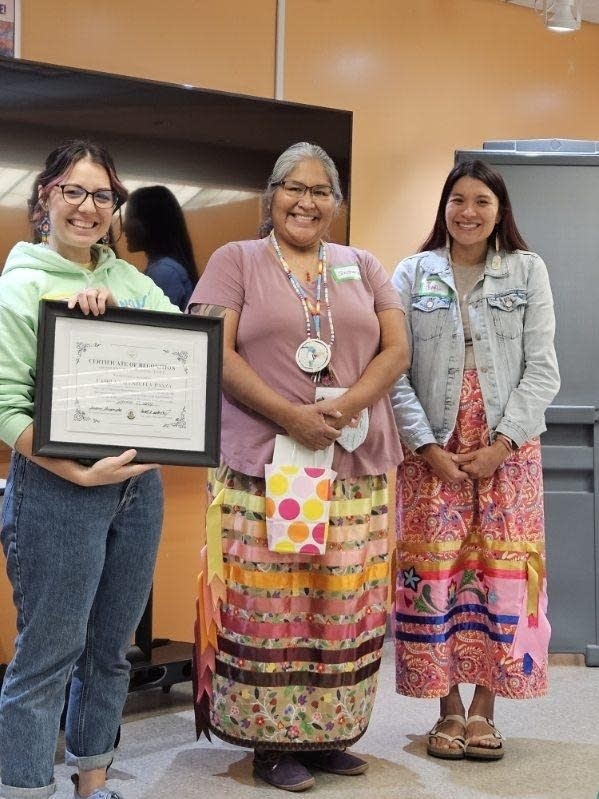

This year’s event, hosted by the coalition, consisted of a discussion on perinatal mood disorders, healthy eating and partner support. The outcome of the event, and the coalition itself, helps other Indigenous people in these roles know there is support available for them too — and that they are not alone in wanting to make a difference, Walker-Swaney says.

“I always think, wouldn’t it be great if every family understood what I understand about breastfeeding? We want it to be so normal and so common to breastfeed that the word ‘lactation counselor’ doesn’t make sense anymore.”

Pasteurized Human Donor Milk is free for the Native American community through Nitamising Gimashkikinaan.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·