ARTICLE AD BOX

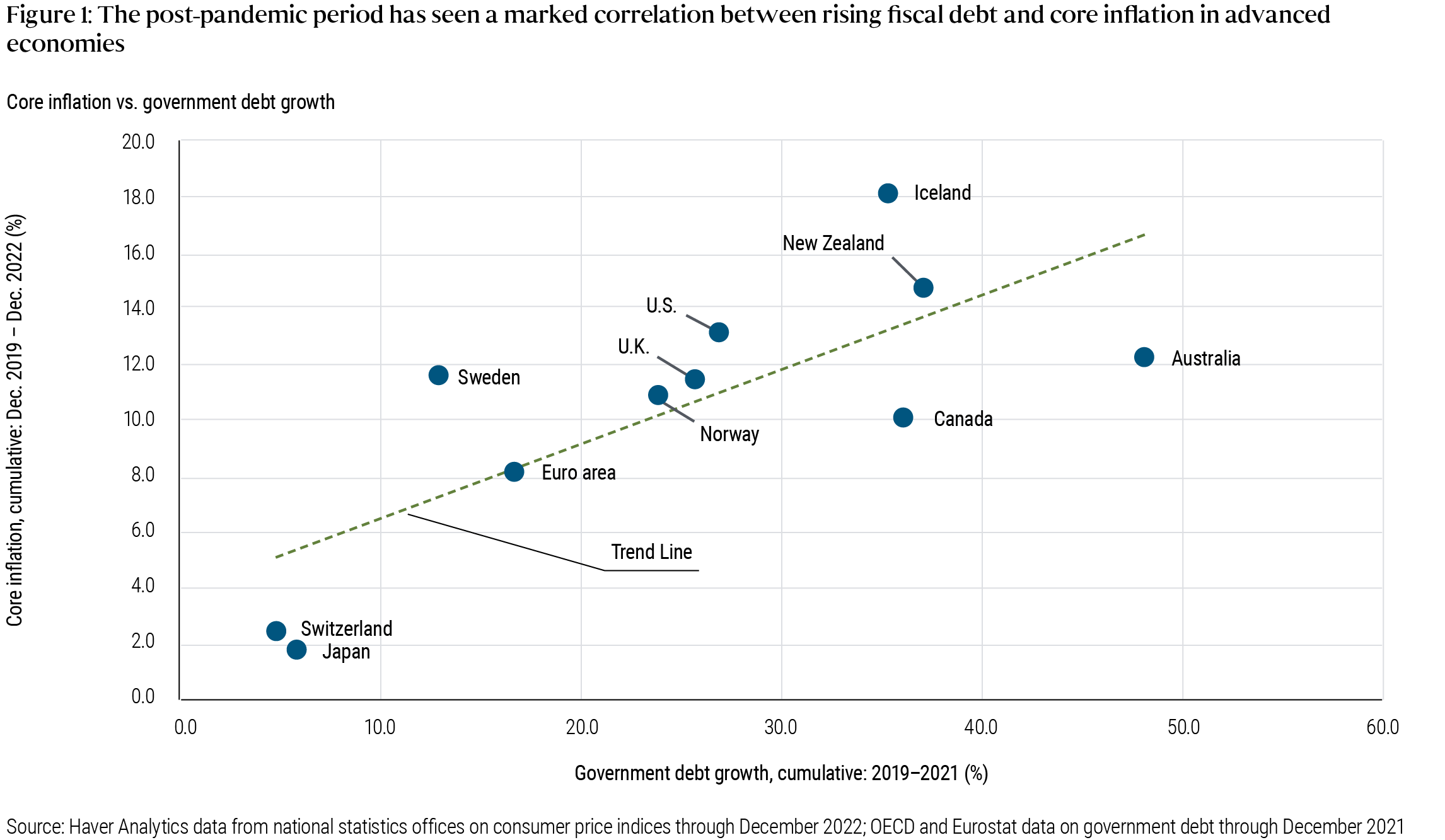

Peder Beck-Friis and Richard Clarida at Pimco have a nice blog post on the recent inflation, including the above graph. I have wondered, and been asked, if the differences across countries in inflation lines up with the size of the covid fiscal expansion. Apparently yes.

It's a simple fact, and it's dangerous to crow too loudly when things go your way. Fiscal theory says that inflation comes when debt or deficits exceed expectations of a country's ability or will to repay. The latter can differ a lot. So, it does not predict a simple relationship between debt or deficits and inflation. Still, it's nice when things come out that way, and more fun to write qualifications than to come up with excuses for a contrary result!

I have seen other evidence that doesn't look so nice (will post when it's public). One example is across eurozone countries. But that's a good reminder where to expect success and where not to expect success. Inflation as described by most macro models, including fiscal theory, monetarism, etc., is the component common to all prices and wages. It is in essence the fall in the value of currency. In any historical experience we see lots of relative price changes on top of that, in particular prices over wages. Indeed inflation is only measured with prices, and a central idea is to measure the "cost of living," not the value of the currency. Across the eurozone there is only one currency and thus only one underlying inflation. The large variation in measured inflations are relative prices, real exchange rates between countries, and can't go on forever. That we cannot hope to explain inflation variation across countries in the eurozone with a simple theory that describes the value of currency gives you some sense of the error bars in this exercise as well.

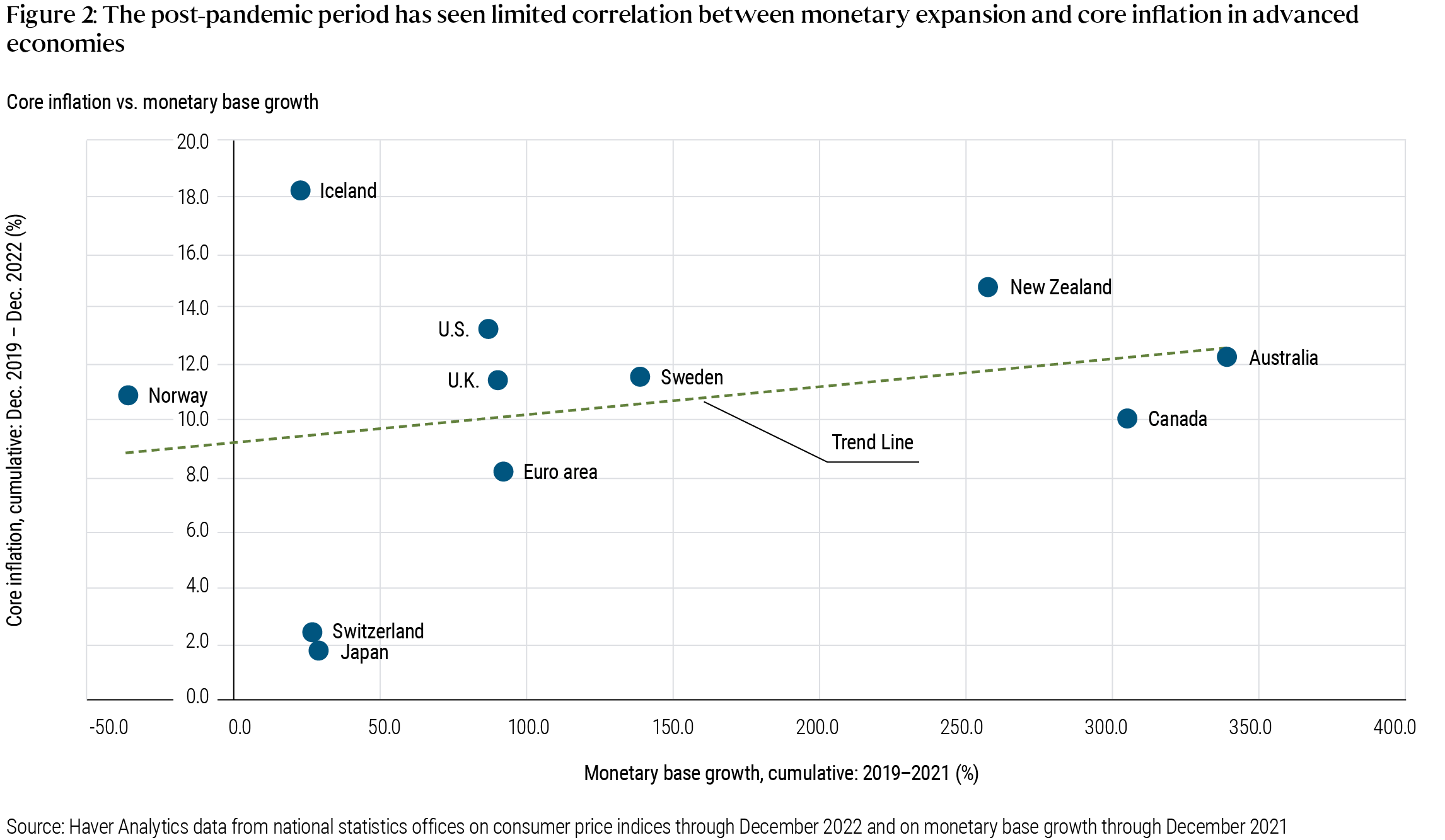

Beck-Friis and Clarida also look at money growth, above. There was a big expansion in M2 before the US inflation. Monetarists took a victory lap. M2 has since fallen a lot. There is not much correlation between monetary expansion and inflation across countries however. The slope of the regression also clearly depends on one or two points.

Money or debt, which is it? When governments print money to finance deficits (or interest-bearing reserves), fiscal theory and monetary theory agree, there is inflation. Printing money (helicopters) is perhaps particularly powerful, as debt carries a reputation and tradition of repayment, which money may not carry. A core issue separating monetary and fiscal theory is whether a big monetary expansion without deficits or other fiscal news would have any effects. Would a $5 trillion QE (buy bonds, issue money) with no deficit have had the same inflationary impact? Monetarists, yes; fiscalists, no.

Beck-Friis and Clarida opine that fiscal stimulus is over and central banks now have all the levers they need to control inflation. I'm not so sure. The US is still running a trillion or so deficit despite a 3.6% unemployment rate, and here come entitlements. And, as blog readers will know, I am less confident of the Fed's lever. We shall see.

Update:

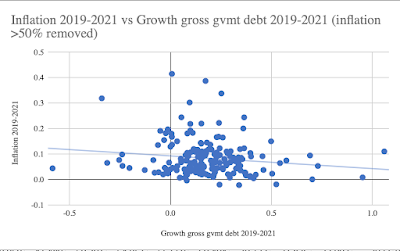

Mark Dijkstra makes the following graph (see comments for link), based on IMF data for all countries. Hmm, doesn't look so good.

However, when you look at lots of small countries, weird things happen. The far right data point is Estonia, with 100% increase in debt and 14% cumulative inflation. Estonia started with 8.2% debt/GDP, however, so its rise to 18.4% is a 100% rise in debt to GDP ratio. So, Estonia spent 10% of GDP on covid and now military, compared to 30% of GDP for the US. Again, fiscal theory is not debt or deficit = inflation, but debt vs. ability and will to repay. One can argue that this increase in debt is more repayable. Argentina has -8% growth in debt/GDP and 100% inflation. Inflation is inflating away debt/GDP faster than the government can print the debt. The high inflation countries in this graph are Uzbekistan, Ghana, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Turkmenistan, Nigeria, Zambia, and Haiti. They are all plausibly fiscal inflation, from preexisting fiscal problems, not stable countries that suddenly borrowed/printed 30% of GDP with no plans to pay it back, the rather special case of the US, EU, UK. OK, I'm making excuses and I'm glad I started with the cautionary paragraph. Fiscal theory is not so easy as debt = inflation! But we do have to confront the numbers, and I hope this spurs some more serious analysis.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·