ARTICLE AD BOX

Minneapolis fiber artist Tia Keobounpheng is taking her work to New York’s legendary Armory Show, one of the leading international contemporary art fairs.

“Point blank, it's a really big deal,” Keobounpheng says. “For me, in my journey, I've been thinking a lot about women and women artists and especially women artists who work in fiber.”

This will be Keobounpheng’s first solo show in New York, which will run Sept. 4-7 at the Javits Center.

A Minneapolis gallery, Weinstein Hammons, will host the booth presenting Keobounpheng’s work. (Weinstein Hammons presented the work of another Minneapolis artist, photographer Alec Soth, at the Armory Show in 2024.)

“Tia's work is truly singular,” says gallerist Leslie Hammons, who will be on site.

Hammons points to Keobounpheng’s background: She spent decades working in the fields of design and architecture (Keobounpheng’s father is the prominent Minnesota Architect David Salmela).

“As a trained architect, her work is meticulous in design and execution, all the while being deeply connected to the idea of women's embodied labor, as well as her Finnish and Sámi heritage,” Hammons says.

Art with a capital ‘A’

Keobounpheng says participating in the Amory Show is particularly significant because as a 20-year-old art student, she recalls a professor telling her that “women working in fiber will never be taken seriously in the capital ‘A’ art world.”

So, the artist says she took a “20-year detour into architecture and design” before returning to the medium in her 40s. Keobounpheng is now part of a fiber arts resurgence, or as the New York Times Style Magazine declared in a 2023 headline: “Fiber Art is Finally Being Taken Seriously.”

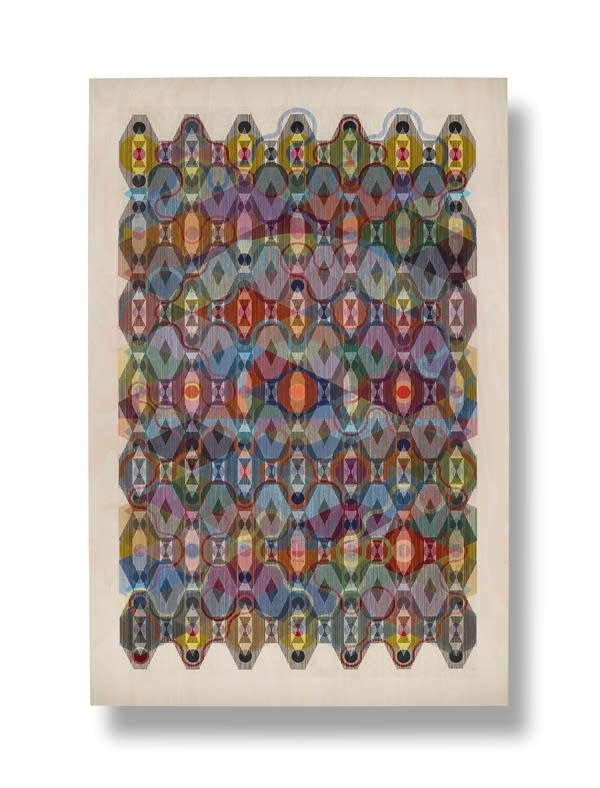

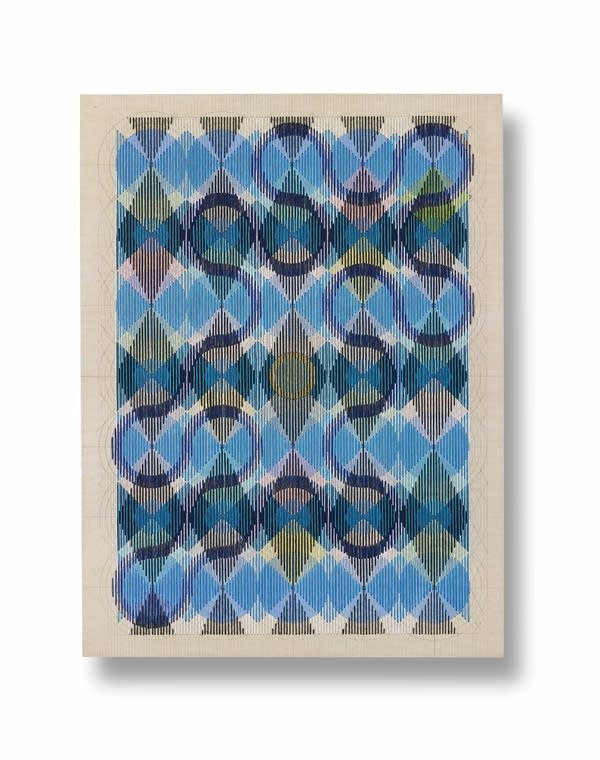

Today, Keobounpheng has developed her own visual language, working in the overlapping realms of color, geometry, abstraction and fiber, creating woven multilayered pieces using jewel-toned thread, colored pencils and wood boards.

Her work was on view for the 2023 exhibition “Tia Keobounpheng: Revealing Threads” at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Weinstein Hammons gallery also presented Keobounpheng’s work at the Expo Chicago art fair last spring.

Forgotten threads

With a small team, Keobounpheng created about 20 pieces for the Armory Show during six weeks this summer. The new body of work is called “muitit,” a Sámi word that means “to remember.”

“It touches on remembering forgotten threads and lineage and ancestors, and it speaks to the land of my ancestors, the forest floor, the tundra, the fjords, the midnight sun,” Keobounpheng says.

Keobounpheng has always been aware of her Finnish heritage, but it wasn’t until a few years ago when researching her family tree that she discovered her family’s Sámi lineage. The Sámi are an Indigenous people of Finland, Sweden, Norway and the Russian Kola Peninsula whose history dates back millennia.

“This has been hard work. I am tracing and examining and reconciling family stories and family lines and people that were almost entirely erased from our family knowledge,” Keobounpheng says.

“I grew up thinking we knew everyone, who we came from, because they were all from Finland. And it turns out that's not true.”

She points to the forced assimilation of the Sámi people through “Scandinavization” policies.

“It's not that people were telling me lies,” Keobounpheng adds. “It was that they didn't know, either, because of forced assimilation, and because it became advantageous for my ancestors to not be Sámi and to be Finnish.”

Meditations about memory

The pieces in “muitit” are a continuation of her “Threads” series, where Keobounpheng threads geometrical tapestries as an act of meditation about memory, both ancestral and in the body.

“Geometry becomes this universal language that I believe our bodies understand, that our bodies can respond to and viewers can have a physical reaction to the work that doesn't immediately make sense in their brain,” Keobounpheng says.

”That's part of that remembering.”

“Muitit — to remember” will be on view in Booth 205 at the Javits Center in New York.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·