ARTICLE AD BOX

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act into law 90 years ago this month. For the first time, workers in the United States had the right to organize unions and bargain collectively.

The law was influenced, in part, by a landmark 1934 Minneapolis strike organized by truck drivers with the Teamsters Local 574.

It was an outcome that seemed all but impossible in the first part of the decade.

America was deep in the Great Depression. And Minneapolis wasn’t exactly friendly to unions.

The city had the reputation as an “open shop town” — where employers didn’t have to deal with organizing. Large employers banded together to form a “Citizen’s Alliance” to keep things that way.

“They got the banks to commit that if you were a business and you wanted a loan from the bank, you could not be in a union contract,” said Peter Rachleff, a labor scholar and retired professor at Macalester College.

“And so they became the enforcement mechanism at sort of creating a solidarity among the employers.”

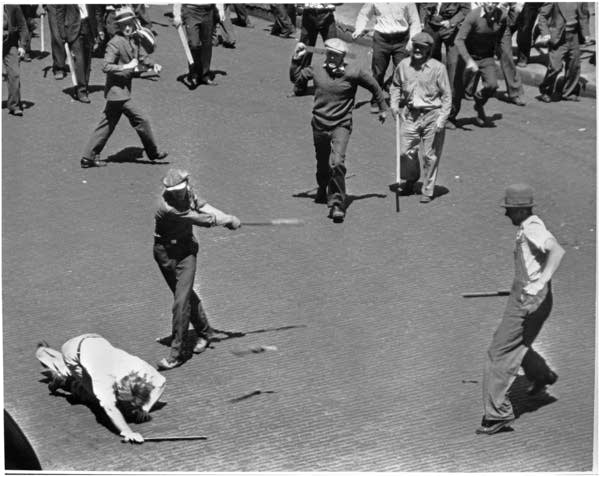

Strikes happened, but were often shut down quickly and physically.

“Labor activists were aware that they could face a group of armed peoples who might be cops, who might be private security, who would try to bust up a picket line and then encourage the unemployed to come and take jobs,” Rachleff said.

In May 1934, the Minneapolis Teamsters decided to try something different. They called a general strike, bringing the city’s drivers and warehouse workers together.

Rather than picket outside of one industrial building, the union used what it called “flying pickets” — gathering wherever a business might try to open a warehouse or run a truck.

The Teamsters — all men back then — formed an intentional alliance with the unemployed, encouraging them to join their cause rather than break the strikes and take their jobs.

Their wives set up a headquarters to serve food and provide round-the-clock care to strikers.

Union organizer Harry DeBoer was around 31 years old in 1934. He recalled the strikes in a 1988 interview with the Minnesota Historical Society.

“Matter of fact is we were in a position to win the strikes because we’ve got the ... rest of the workers to put heat on these old bureaucrats who are satisfied sitting there doing nothing,” DeBoer said.

The union had essentially shut down the industrial area in what is now known as Minneapolis’s North Loop. Trucks couldn’t go in or out. But the employers would still not agree to a deal.

The conflict came to a head on July 30, 1934.

Police opened fire on protesters near the corner of 7th Avenue and 3rd Street North.

Teamsters organizer Jack Maloney recalled the clashes in a 1988 interview with the Minnesota Historical Society. He said he figured the strikers might get minor wounds — but did not expect to see police shooting at them with riot equipment. He was in his early 20s in 1934.

“There's a guy across the street and he had this goddamn riot gun, and we come around the corner and he fired,” Maloney said.

“He shot the leg out of Harry DeBoer, and Ben's arm was almost severed… and I got the rest of it in my chest. And I thought I was f****** well killed.”

After the dust settled, 67 unarmed workers had been shot, and two were killed.

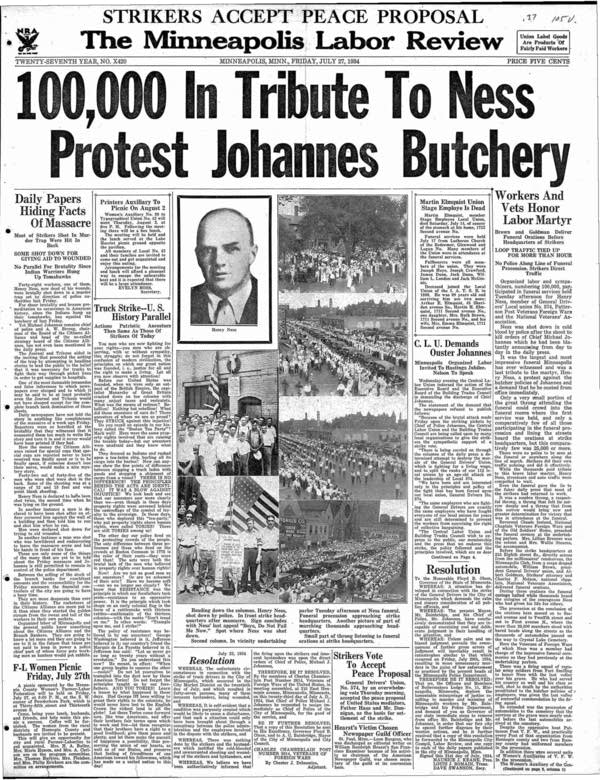

Tens of thousands of people lined the streets for the funeral of Henry Ness, a 40-year-old veteran of World War I. The Minneapolis Labor Review reported Ness had been shot twice, once while lying down, and most of the picketers had been shot in the back.

The violence drew international sympathy and the Citizens Alliance eventually yielded to the pressure, making the strike a success.

As worker Earl Sunde recalled in the 1981 documentary, “Labor’s Turning Point,” he received a raise from $18 a week, or about $436 in today’s dollars, to about $33 a week, or $800 today.

“So we could probably take care of our families a little bit better, because we was working a 48-hour week, and for $18 a week we just weren't making both ends meet .”

The Minneapolis strike signaled to other workers across the state and across the country that their strikes could work, too. It proved that workers still had power during the Great Depression. A wave of other strikes followed in Minneapolis and across the country.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·