ARTICLE AD BOX

Along a gravel road in rural Mower County, amid the emerald rows of corn, is a sign that reads, “Grand Meadow Chert Quarry - Wanhi Yukan Trail.”

Wanhi Yukan is the Dakota name meaning “There is chert here.” Next to the sign, a walking trail leads into a tall grove of oak trees.

Chert, sometimes called flint, is the stone Indigenous people customarily used to make everyday tools.

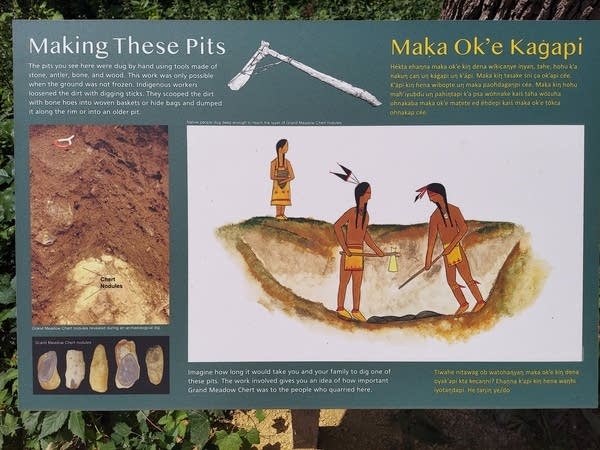

Shaded by the oak trees along the walking trail is another sign offering both an archaeological and cultural interpretation of the site.

The work to create the preserve is a partnership among Mower County Historical Society, Prairie Island Indian Community and The Archaeological Conservancy, a national organization.

Franky Jackson is a compliance officer for Prairie Island Indian Community, a Dakota nation located in the southeastern part of the state. He’s also a tribal member from the Sisseton Wahpeton Sioux community in South Dakota.

“I always imagine this as being one of the last stops for you before you pushed out onto the plains and you went hunting buffalo and all of that. This was one of your last stops to sharpen up your tools, get everything you needed,” Jackson said.

The ancestors of the Dakota, Ioway and Ho-Chunk tribal nations came to this area in present-day Minnesota to quarry stone approximately a thousand years ago.

The eight-acre preserve consists of more than eight pits, some of which are up to 15 feet deep and more than 20 feet wide. The existing quarry is what remains of what archaeologists believe was a much larger site with more than 2000 pits.

Archaeologist Tom Trow co-led the work to preserve the site. He published several research papers detailing the quarry’s archaeological history.

Trow said archaeological records indicate Indigenous people have been coming to this site for 8,000 years. Trow theorizes that people likely gathered what they needed from the nearby riverbank or the surface of the land. Trow said that changes in agriculture that took place about 1,000 years ago created a demand for high-quality stone, and people began to quarry the material.

“This is the best stone in Minnesota for creating hide scrapers, this Grand Meadow chert. So, we know they came here for that purpose. Because when we go to the archaeological sites along the Mississippi River, along the Cannon, along the Blue Earth, the villages there that have Grand Meadow chert and have a lot of it,” Trow said.

The preserve has created a self-guided tour with signage in English and Dakota. The signs serve as waypoints for visitors to learn about why the material was important to people.

Jackson says he remembers that the work to design and interpret the area began when Dakota elders first visited the site.

“It was a real, kind of a really magical moment to hear those thank you songs coming from the site in here. And it to me, it kind of woke up the site, if you will and it reignited this curiosity, not only within us, but with others who were standing with us that day,” Jackson said.

One such sign describes how bison provided nearly everything that people needed, but only if they had hunting weapons, butcher knives and hide scrapers — tools made from chert. The preserve has also enlisted the help of a handful of artists to help people imagine what the quarry might have looked like when it was at its most active about 700 years ago.

In addition to the bilingual signage, Jackson and his team created instructions for people to leave prayer ties and tobacco, an act of gratitude and respect.

“It makes Natives visiting the site feel welcome. If there is a designated area for you to leave your prayer ties and your offerings, that’s wonderful. That's making accommodations for those people out that have deeper ties to this landscape,” Jackson said.

Maynard Green’s theory

In the neighboring town of Austin, a local history exhibit tells the story of how the quarry was kept from being plowed over for farmland.

Inside a permanent exhibit at the Mower County Historical Society, rows of arrowheads and spear points made from Grand Meadow chert fill gleaming glass display cabinets. The artifacts were donated to the county by the late Maynard Green, a collector and amateur archaeologist. The entire collection consists of over 800 artifacts, and many of the tools were collected within a short distance from the quarry.

Also on display is a copy of a letter Green wrote to the state archaeologist in 1952, inviting him to visit Grand Meadow to survey the site.

A copy of Green’s letter is part of the exhibit.

“There is a locality near here that has puzzled me for a number of years. It is in a small patch of timber. The timber being there because the ground is too rough for cultivation,” wrote Green.

In writing the letter, Green hoped to confirm his theory about why the area was so rich in stone artifacts.

“Around this patch of timber, there seems to be an abundance of gray or whitish Flint. It is my theory that this is an old Indian Flint quarry. Could this be possible?”

The state archaeologist did pay Green a visit, but an impending storm kept him from visiting the chert pits. It would be years before Green would receive another visit.

Randal Forster, executive director of the Mower County Historical Society, motioned to a timeline painted on the walls of the exhibit that stretches from a point in time more than 10,000 years ago up to the present. He said the quarry and the county’s exhibit helps to connect visitors to a much older story.

“You kind of see how our little piece of Mower County fits into this grand scheme of world history,” Forster said.

It was just a few years later, in 1980, Trow was working on an archaeological survey in the area when he found Green’s letter. Trow and colleague Lee Radzak paid a visit to Green who was still living in the area.

Their visit and the research that followed spurred The Archaeological Conservancy to purchase the site in 1994. That same year, the site was added to the national registrar of historic places.

A collaborative process, Indigenous led

A few years ago, Trow was giving a presentation to members of Mower County Historical Society and suggested the group consider putting in a walking trail through the quarry.

Trow says the historical society didn’t have a large enough budget to take on the project, so he decided to take it on himself.

He said he worked from the start to gain support from the local community in Grand Meadow and from tribal nations in the area.

By then, Trow had worked for a couple of decades at the University of Minnesota leading the institution's work with tribal nations on repatriating cultural items. Trow said his work on repatriation issues transformed his perspective on archaeology as a field.

He says his work at the Grand Meadow Chert Quarry was conditioned on having Indigenous people involved in the project.

“There’s a saying within the communities that I really take to heart, their saying ‘it’s never about us without us,’” Trow said.

The team from Prairie Island Indian Community led the effort to determine how research at the site will be conducted.

“We also have some wonderful technology that we can also turn to with regards to less intrusive archaeology. So, employing geophysics here on site will be one of the main tools that will be used going forward,” Jackson said.

On a recent trip home to Sisseton, S.D., Jackson snapped a photo of a spear point he found at a fishing site. He recognized it right away. It had been made from chert quarried at Wanhi Yukan. He was excited to share his find with Trow.

“We have a responsibility to learn as much as we can and then share that knowledge with others,” Jackson said.

As he takes a look around the quarry, Jackson says he’s still processing what it all means.

“It just invokes all of this curiosity in my mind. And again, I’m still kind of processing how neat it feels to be able to touch something that your ancestors touched thousands of years ago.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·