ARTICLE AD BOX

Nearly every week for three years, as the morning light crept over the horizon, Addie Evans climbed into her Subaru Outback, iced coffee in hand. The Cranberries played through the speakers as she turned up the volume and set off on the familiar drive north, leaving behind the rolling hills of Mankato for the Twin Cities metro.

The Subaru was more than just Evans’ transportation. It also doubled as a mobile office, packed full of lists, a journal, her laptop, gloves, birth control pills, condoms and packages of misoprostol, a medication that can be used to end a pregnancy.

As a senior health center manager for Planned Parenthood North Central States, Evans oversaw daily operations at the Mankato clinic and supervised managers across eight regional sites. She played a key role in bringing abortion care to the Mankato clinic and occasionally stepped in as interim manager when other clinics needed extra support.

“This work was really important to me,” Evans said. “I saw myself working there for the rest of my career.”

But Evans quit last summer after growing frustrated with what she saw as upper management’s lack of responsiveness to staff complaints about workplace culture and patient care.

“My goal was always to share the concerns and the voices of the staff that I worked with,” Evans said. “It was absolutely heartbreaking the way it ended for me.”

The overturning of Roe v. Wade, the reelection of President Donald Trump and attacks from Republican-controlled state governments have created dire financial conditions for abortion providers nationwide. And St. Paul-based Planned Parenthood North Central States, which serves patients in Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota, is no exception.

But external pressure is only part of the story. Conversations with eight current and former employees reveal that the organization is also experiencing internal strain, with at least seven internal complaints about management over the past two years.

Multiple staff members expressed discontent with executive leaders and top managers. They characterized the work environment as disrespectful and chaotic. And they described what they saw as efforts to silence internal dissent that they said are contributing to the difficulties at Planned Parenthood North Central States.

Their concerns echoed those raised at the organization’s Omaha clinic earlier this year, as detailed in an article published by the Flatwater Free Press, an investigative news outlet covering Nebraska. The article, based on interviews with seven current and former staff, reported complaints about short staffing, “chaotic management” and “unresponsive out-of-state executives,” allegations that Planned Parenthood North Central States denied.

“I’m not going to say that everything is easy or perfect, because it’s not, but I do stand by the fact that our team works really hard to not only hear our staff, but their ideas for innovation as well,” CEO Ruth Richardson said during an interview with MPR News. “Issues like this arise, but overall, we are working really hard to ensure that we’re meeting the needs of our patients.”

Richardson, an attorney and former DFL state representative, took over as CEO in 2022 from the organization’s previous leader, Sarah Stoesz. Before this role, Richardson led Wayside Recovery Center, a St. Louis Park-based mental health and substance use disorder treatment provider with a staff of fewer than 200 employees — less than a quarter of the size of her current organization.

Alleged ‘toxic management’ at Planned Parenthood North Central States

Evans worked at Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains and at an affiliate in southwestern Oregon before she joined Planned Parenthood North Central States in 2021.

Her weekly drives were more than routine. They were a vital part of providing support to staff and making sure that patients had access to care. She would visit clinics on days when they were providing abortion care or when there was a need for front desk coverage due to lean staffing.

“There was always at least one clinic that did not have a manager,” Evans said. “And there was a lack of resources and lack of support for what we were doing on the ground.”

Evans said that seeing as many patients as quickly as possible was becoming a priority. Typically, Planned Parenthood North Central States aims for each health care provider to see three patients per hour for various reproductive health services. While this approach allows clinicians to serve many patients efficiently, Evans expressed concern that it compromises the quality of care.

“After COVID, people would come in and be like, ‘I think I’ve had BV (bacterial vaginosis) for six months, and now it is a kidney infection,’” Evans said. “The complexity was growing, but the time allotted to see the patient was not. Patients would say, ‘I’m not going to come here anymore; I’m going to see my primary care provider’ or ‘I’m going to go online and order my medication.’”

When employees expressed their disagreements and raised concerns about patient care, Evans said that these situations became confrontational. She was asked not to communicate with other staff members and to present a united front. After voicing her dissent, she said she was labeled a troublemaker and her situation deteriorated rapidly.

“Then it was also just kind of trying to keep staff happy with really toxic management,” Evans said.

High staff turnover made it increasingly difficult for Evans to do her job effectively, so she started searching for another one.

On May 16, 2024, she submitted a resignation letter with the customary two weeks’ notice, but four days later a director of human resources said her termination was effective immediately. The director told her not to return to the workplace due to complaints made by another staff member.

Evans was stunned. Her personnel file contained no write-ups or negative performance reviews. Evans still doesn’t know exactly what the complaint was about or who raised it.

“I care so much about the mission, and I moved to Minnesota for this job. I care about reproductive health access for people all across the country,” Evans said. “It was just devastating.”

Federal funding cuts force clinics to close

The internal strife at Planned Parenthood North Central States came amid a time of financial stress. In May, the organization announced it was closing 8 of its 23 health centers and laying off 66 employees. The clinic closures and consolidations affect an estimated 90,000 patients.

Planned Parenthood clinics provide free medical care to patients who cannot afford it and offer a range of services including the abortion pill, annual exams, cancer screenings, vasectomies, birth control, sexually transmitted infection testing, vaccinations and prenatal care. Of the 15 clinics currently operating in the region served by the organization, only three provide abortion procedures on-site.

The organization’s announcement said that federal funding cuts and an under-resourced health care system contributed to the situation. A press release pointed to several factors, including frozen federal grant funds in Minnesota through a program called Title X and cuts to Medicaid, as well as changing patient needs, clinic reimbursement rates and rising costs.

But the financial troubles had been brewing for years. In 2018, Planned Parenthood Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota announced it was combining operations with Planned Parenthood of the Heartland to form Planned Parenthood North Central States, which now serves as the parent organization for the two subsidiaries. Staff members said that the integration of the two organizations came with its own set of financial hardships. Publicly available tax returns indicate that both organizations were operating at a loss before joining forces.

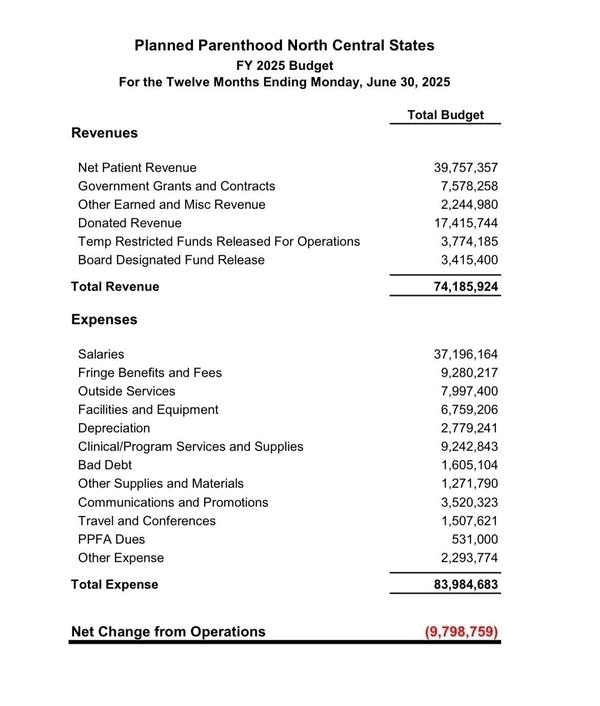

The combined entity operated in the black for its first five years, but in fiscal year 2024, the organization’s tax forms show revenues dropped and expenses rose, resulting in a deficit of nearly $3 million. Internal budget documents shared with MPR News show the organization projected a $10 million deficit in fiscal year 2025, which culminated in the clinics closing.

Officials at Planned Parenthood North Central States said that the budget document is inaccurate in its details, and the actual results have not yet been finalized or audited, but the organization did face a multi-million-dollar deficit.

Richardson said that the entire health care ecosystem was on life support when she took the job in 2022, and the organization was facing “a perfect storm of intense financial struggles and unrelenting attacks on health care.”

“Our team has been doing really hard work year over year to be able to get to a point to have a break-even budget for FY26, but it was a long hard road, and I can’t overstate that,” Richardson said.

Layoff followed hostile work environment allegation

Melissa Forsyth, former senior director of health centers at Planned Parenthood North Central States, had to escort Evans out of the Mankato health center on Evans’ last day. Seven months later, she would be escorted out herself, following a layoff.

Forsyth, who was also interviewed for the Flatwater Free Press story, described the workplace culture as “terrible” and “increasingly toxic.”

She recalled a meeting that included the human resources department, the recruiting department, and chief operating officer Sheilahn Davis-Wyatt. During this meeting, Davis-Wyatt insisted that a bachelor’s degree should be a requirement for health center managers. Forsyth disagreed, pointing out that she did not have one. She felt offended when Davis-Wyatt then questioned whether people without such a degree had the necessary math skills to do the job effectively.

Forsyth said that other situations at work felt “gross” to her, so she filed a grievance alleging a hostile work environment.

A few months later, the human resources department told her that the investigation concluded “it was not hostile; it was disrespectful,” Forsyth said. “Then I got laid off three months later.”

In January, her position was terminated as part of a restructuring designed to cut costs by consolidating management positions. But for Forsyth, it felt personal.

“I was seen as being a rabble-rouser and eventually just told it’s time for you to go,” she said.

Richardson said the elimination of Forsyth’s role was about the organizational structure, not about job performance or retaliation for complaints.

Email resignation draws reactions, rebuke and apology

A former employee, who asked to remain anonymous, submitted three separate complaints to human resources about how a manager was treating people in her department. She also sent an email directly to Richardson, urging her to pay attention to staff concerns.

Her manager “would threaten me with if you don’t react to my Teams messages in the morning, you will find out what happens to you, and that will be your choice,” the employee said. “I’ve also been told that my opinions do not matter, because (the manager) will be in charge of making the final decision anyway.”

In June, the employee quit.

“There has been no accountability, no effort to stop the damage. Just willful, complicit silence,” she wrote in a mass email to her colleagues on her last day of work. “I could give specific examples, but HR has allowed this to continue so it must be okay to come to work and be threatened, harassed, belittled, and degraded.”

She wrote that working for the organization “was once a dream of mine,” concluding “after this, I will never work in reproductive health care ever again.”

Some staff members reacted to the message with heart emojis, a feature of the Microsoft email system. In response, Andrea Schossow, director of patient engagement, emailed them. She called the original email message “disgusting” and demanded to know why they had expressed support for it. “If I don’t receive an explanation by the end of the day or the explanation provided is not satisfactory, we will be meeting in person to discuss,” she wrote.

About an hour later, Schossow sent another email to apologize, acknowledging that her earlier message “could have been received in a way that felt intimidating or retaliatory.” She added that the organization “has a policy that prohibits retaliation and encourages good faith reporting of concerns. To the extent my email had a chilling effect on raising concerns, I am truly sorry.”

Richardson said she cannot justify Schossow’s original email but called the apology “an example of how we are elevating things within this organization.”

“We are responding,” she added. “And we’re responding promptly.”

A complaint to the board and Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Another employee who asked not to be identified, sent two emails expressing concerns about the leadership at Planned Parenthood North Central States.

“We have a fractured Executive Team,” they wrote in a May 28 email to Planned Parenthood Federation of America, the national parent organization that supports independently incorporated Planned Parenthood affiliates. The email alleged that staff were “being ‘restructured’ out because they push back on the COO,” referring to Davis-Wyatt. “We have no one to turn to.”

The employee sent a second email to the board of directors of Planned Parenthood North Central States later that week.

“I am hiding my identity out of fear. Fear for myself and my co-workers,” they wrote. “The board needs to be more involved. They need to work with the staff. Talk with us. We all want the same thing. But many worry that those goals cannot be achieved under the current operations leadership.”

Sarah Rozensky, a lawyer in the general counsel’s office at the national organization, responded to both emails.

“Thank you for reaching out,” Rozensky wrote both times. “I will share your concerns with leadership.”

Richardson said these emails followed a “heartbreaking restructure” that resulted in the layoff of 66 colleagues.

“Change is hard on a good day,” Richardson said. “And so, to see this coming out days after the restructure, it’s not surprising to me, because people were processing through a lot of pain and through a lot of grief.”

A former employee who left Planned Parenthood North Central States in the summer of 2024 after nearly a decade of working at clinics in the Twin Cities said that the organization consistently operates on the brink of crisis. They believe that this environment allows inappropriate behavior among management to be overlooked.

“I cannot tell you the number of times I heard, ‘In the future, this will be different,’” they said.

Evans, the former senior health center manager for Planned Parenthood North Central States, said that after the layoffs in May, a number of departing employees told her their experiences working for the organization were “horrible.”

“I do believe that Planned Parenthood will go away. And that is a really sad thing to say,” Evans said. “Patients and staff need to be at the center of the movement, and unfortunately, they are being pushed out.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·