ARTICLE AD BOX

by Katrina Pross and Becky Z. Dernbach, Sahan Journal

The young boys played video games, billiards, air hockey and Nerf basketball in their coach’s basement in Brooklyn Center. He gave them pizza, burgers, chips and soda.

Sports memorabilia decorated the walls alongside trophies, medals and plaques from tournaments. A poster was inscribed with the boys’ basketball team name: “Kings of the Court.” They slept over the night before games. He took them to Timberwolves games, picked them up from school or home in a van for basketball practice.

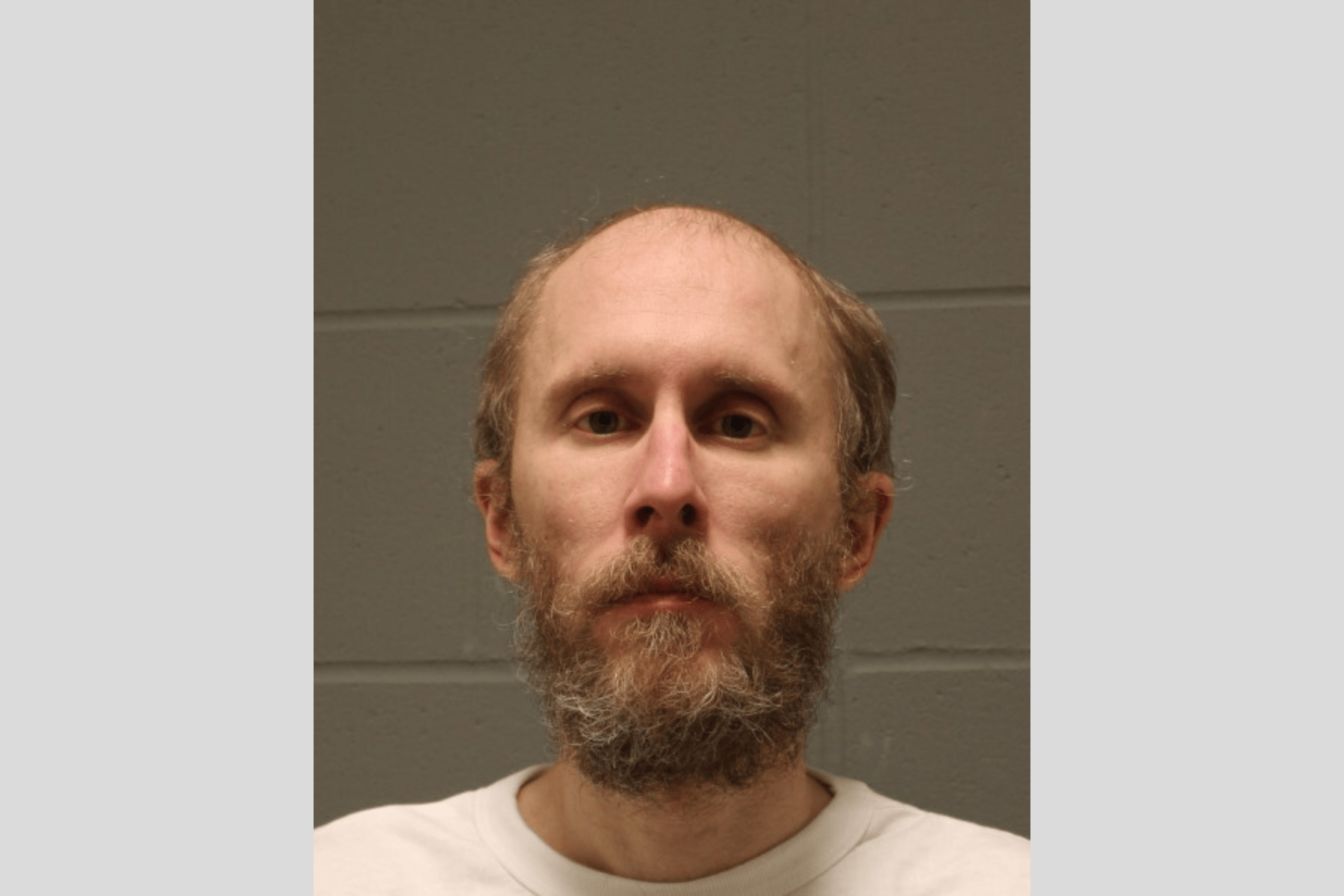

Staying at coach Aaron Hjermstad’s house seemed like a young boy’s paradise. But in order to participate, many of the boys endured a nightmare. Four of them reported to law enforcement that he had sexually abused them. Authorities say there could be more than 120 victims.

One of those boys was Jazz, who was an 11-year-old sixth grader when the abuse started during the 2014-2015 school year.

He spent the night at Hjermstad’s home after a group trip to a Timberwolves game in 2014. Hjermstad told him that night that he should sleep in his room. The boy awoke in the middle of the night to find his hand forcibly placed on Hjermstad’s genitals.

A few months later, he woke up to find Hjermstad looking up his shorts with the light from a cell phone. Hjermstad was on the floor. When Jazz asked why, he said he had heard a noise and wanted to keep the boys safe. Jazz and other teammates stayed up all night that evening, fearing Hjermstad would touch them.

“I didn’t go to sleep because I thought of what happened last time,” Jazz, then 12, told a forensic interviewer who spoke with him in 2015 as part of a police investigation into the incident. “I stayed awake.”

Jazz did what he felt was right, what he thought would put a stop to the abuse — he told a trusted adult at his school, Excell Academy, a charter school in Brooklyn Park. The police investigated.

Then the unthinkable happened: Hjermstad, now 46, wasn’t charged. He got a new job at another charter school. He kept coaching and abusing children.

Jazz, now 22, still has difficulty talking about what happened to him. His mom, Alexis, wanted to share their story to help people understand the importance of believing children when they report abuse. Their names have been changed to protect their identities because Jazz was a minor when he was abused. At times during interviews with Sahan Journal, Jazz rested his head on the family’s kitchen table. On another occasion, his fiancee wrapped an arm around him for comfort.

“I feel kind of played a little bit,” Jazz said, referring to authorities’ decision not to charge Hjermstad for abusing him. “I took the time out of my day to go tell something that was bad, but for a good cause, which was to get it to stop. But they didn’t do anything about it.”

Jazz and his mother believe the abuse and pain the other boys suffered could have been prevented if something had been done in 2015.

“This is not just something that happens one time to a kid and then they deal with it. My child, now an adult, is still dealing and suffering behind it,” Alexis said. “They dropped the ball. I believed my son from the beginning, but to hear that there was more boys, and then there’s more boys, it’s just like, are you kidding me?”

Jazz and Alexis’ experience raises questions about charter school employment practices, and illustrates the challenges of prosecuting sexual assault cases when a child’s word is pitted against a beloved educator. The school, the state education system, police and a local nonprofit launched four separate investigations into Hjermstad after Jazz came forward, but none resulted in any charges or discipline.

Alexis and Jeff Anderson, a St. Paul attorney representing some of Hjermstad’s victims, also say Hjermstad, who is white, deliberately targeted Black boys. Experts say these children are less likely to come forward about abuse, and are less likely to be believed when they do.

“These are kids from communities that aren’t going to report,” said Anderson, who has represented sexual assault victims for decades.

So how did Hjermstad come to abuse more children after Jazz reported him?

The answer lies in loopholes in Minnesota law, challenges in the criminal justice system and the school’s approach to investigating the allegations, experts say.

“By not taking the time and the effort to do the right thing in the short term, it creates this pattern of passing the trash,” said Billie-Jo Grant, the CEO of McGrath Training Solutions, a national organization that trains schools to investigate sexual assault allegations. “Once they [predators] do it once, they’re definitely going to do it again — until they get caught.”

Hjermstad was respected, ‘loved’

Alexis says she was introduced to Excell Academy in the early 2000s through Sabrina Williams, the school’s founder and director. Williams is married to the bishop at Alexis’ church, Mighty Fortress International Church, which she still attends.

Several parishioners worked at Excell Academy, said Alexis, who has been a church member for decades. She enrolled her older son at Excell starting in kindergarten, and Jazz starting in preschool.

“I felt secure, safe and I was able to trust the people,” she said of her impressions of Excell Academy.

She first saw Hjermstad at church. He was well-connected, respected and “loved” in the community, Alexis recalled. His sister also worked at Excell Academy from the school’s founding until 2011.

Hjermstad was a founding member of Excell Academy, and began his career there when the school opened in 2001, after graduating from the University of Northwestern. Records show that he was the school board chair in the spring of 2015, a role he held for three years.

“Everybody knows Mr. Hjermstad,” Alexis said.

Anderson said Hjermstad groomed the entire school community where he coached boys basketball and worked as a gym teacher. Many of the players came from single-parent households. Hjermstad offered to drive the students to and from basketball practice, and built trust among parents.

“Hjermstad was so cunning and clever, and so effective at grooming parents and kids,” Anderson said.

Hjermstad did not return email messages Sahan Journal sent to his Department of Corrections email account. The Hennepin County Public Defender’s Office, which is representing Hjermstad in his current cases, declined to comment because of the pending criminal charges against him. The private attorney who represented Hjermstad in his previous criminal cases did not respond to requests for comment.

Reached by phone and email, Hjermstad’s mother and sister both declined to comment.

The night everything changed

Jazz played basketball at Excell Academy, where Hjermstad also served as his gym teacher. Hjermstad convinced Jazz to join his traveling basketball team at Hospitality House Youth Development, a faith-based non-profit in north Minneapolis. Hjermstad took the Hospitality House team on trips across the country, and also hosted team sleepovers at his home.

Jazz liked playing point guard and shooting guard. Watching the ball fly through the basket and hearing the crowd cheer thrilled him. He played multiple sports, but basketball was his favorite. His eyes light up when he talks about the game.

“It’s refreshing to me, like it makes me feel like I actually can do big things,” he told Sahan Journal.

During an interview with Cornerhouse, where children are interviewed by sexual assault experts as police listen in another room, a 12-year-old Jazz recalled the night Hjermstad told him to sleep in his bedroom after a Timberwolves game. Jazz sat in the small room on a sofa. He looked uncomfortable, but appeared clear-headed and eager to share as the interview progressed. Sahan Journal reviewed video footage of the interview, which is public data as part of the evidence presented in court in Hjermstad’s criminal cases.

Jazz told a Cornerhouse interviewer that Hjermstad said someone had tried to burglarize his home, and that Jazz, the only teammate staying over that night, would be less safe sleeping in the living room. Hjermstad showed him a sharp knife he kept in his room “in case of robbers.”

Jazz said he was scared, and slept on the floor of Hjermstad’s bedroom. He was terrified when he awoke and found his hand on Hjermstad.

He pretended to be asleep so Hjermstad wouldn’t abuse him further. Hjermstad cooked breakfast for Jazz the next morning, but Jazz threw it away immediately. Hjermstad drove him to school.

After Hjermstad looked up his shorts about four months later, Jazz reported the abuse to Eddie Grant, Excell Academy’s equity director at the time.

“I just knew it wasn’t right, and I could already tell that something was wrong with him. I just couldn’t put a finger on what it was,” Jazz told Sahan Journal.

Eddie Grant told Sahan Journal he recalled seeing a “distraught” Jazz at the bus in 2015. Grant asked him what was wrong, and Jazz said Hjermstad had been trying to make him touch him. Grant struggled to get more details out of Jazz, but reported his comments to Alexis as well as Williams, the school’s director (and Grant’s aunt).

Williams reported the incident to police in Brooklyn Park, where the school is located, and the Minnesota Department of Education, as required by Minnesota’s mandatory reporting law. Brooklyn Park police took a report, but Brooklyn Center police investigated Jazz’s allegations because the abuse occurred at Hjermstad’s home in their jurisdiction.

“I thought he was going to rape or kidnap me,” Jazz told the interviewer.

Brooklyn Park police responded to the school on May 6, 2015, and spoke with Williams. The school placed Hjermstad on administrative leave after receiving Jazz’s report.

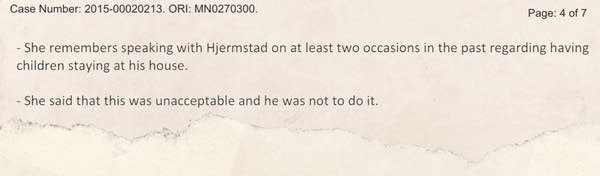

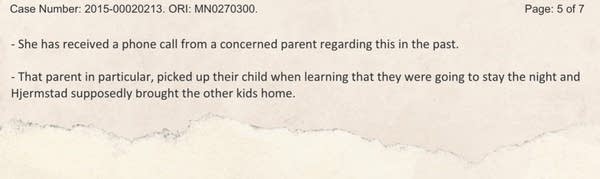

According to the 2015 Brooklyn Park police report on Jazz’s case: Williams told officers that before Jazz had reported him, she had spoken with Hjermstad on at least two occasions about sleepovers with students at his home. She had also previously received a concerned phone call from a parent. She said she had told him it was unacceptable.

“Sabrina knew that he was crossing boundaries, and that he was being inappropriate and that parents had complained about it,” said Molly Burke, an attorney with Jeff Anderson’s office.

Eddie Grant recalled that school staff openly argued over Hjermstad’s sleepovers prior to Jazz coming forward. Some thought he shouldn’t be having kids over, and others thought it was fine, Grant said.

School records show that Excell Academy did not take any disciplinary action against Hjermstad, either for the previous incidents Williams mentioned in the police report or for Jazz’s complaint.

Yelena Bailey, executive director of the Minnesota Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board, said that state law requires schools to notify her agency within 10 days of a teacher’s suspension, including administrative leave, so that the agency can conduct its own investigation. It’s unclear whether that happened in this case, since those records are not publicly available unless the licensing board takes disciplinary action.

Police records show that Excell Academy’s human resources director told police that its board of directors — which Hjermstad chaired for three years before he was placed on administrative leave — was considering terminating Hjermstad based on violations of the school’s conduct code involving sleepovers with children.

But for reasons that are unclear, that didn’t happen. Instead, Excell Academy decided not to renew Hjermstad’s contract for the 2015-16 school year. The school’s letter notifying Hjermstad that his contract would not be renewed did not cite a reason.

“They kept it open for him to be able to work somewhere else,” Alexis said.

Williams did not respond to multiple requests for comment on Excell Academy’s response to Jazz’s allegations. She also declined to speak with Sahan Journal following Excell Academy’s most recent board meeting at the school in June.

“Excell Academy took all lawful actions and had no knowledge that any student of the Academy was involved, harmed or had any complaint. Moreover, it was not contacted by any employer for reference about this former employee,” Laura Booth, an attorney representing Excell Academy, told Sahan Journal in an email statement.

The police investigation

Brooklyn Center police investigating Jazz’s allegations identified other potential victims or witnesses in the case.

Jazz and three other boys who had been coached by Hjermstad were interviewed in 2015 by forensic interviewers at Cornerhouse. Jazz was close with one of the boys, and had told him what Hjermstad had done.

“[He] was guarded and it was apparent that he was not disclosing all information known to him,” Brooklyn Center police detective Terry Olson wrote regarding one of the boys.

“When the questions became more specific and pointed about things to do with sleep overs [sic] and what others may have said about ‘Coach Aaron’ [sic] he became very quiet and evasive. He began fidgeting and would no longer make eye contact with the interviewer,” Brooklyn Center police detective John Ratajczyk wrote about another boy.

Sahan Journal reviewed police reports written by Ratajczyk, who led the investigation, and watched video recordings of the boys’ interviews. Ratajczyk, who has since retired, did not respond to requests for comment.

One of the boys played on a cellphone during his interview, and was reluctant to answer questions. Another shook his head and nodded when responding to questions, speaking with few words.

The boys denied being assaulted by Hjermstad, according to the police report and Cornerhouse interviews. One boy was asked by a forensic interviewer what he would think if one of his teammates said they were abused.

“Not true,” he replied.

Brooklyn Center police executed a search warrant at Hjermstad’s home in May 2015. Ratajczyk wrote in his police report that he believed that Hjermstad could have photos or videos that might provide further evidence to support Jazz’s account. Officers seized multiple cameras, digital memory cards, photo albums and compact discs. Police reports do not indicate if anything was found on them.

Ratajczyk and other officers continued to look for other victims. They knocked on the doors of other boys on the Hospitality House team and spoke with their parents. Ratajczyk wrote that police discussed “instances of questionable conduct” with the boys’ parents, according to Brooklyn Center police reports. But, according to his report, police determined that those interactions did not rise to the level of criminal sexual assault.

Assistant Hennepin County Attorney Cheri Townsend declined to file charges in Jazz’s case, on July 30, 2015, Ratajczyk wrote in a report. After police were unable to identify another victim, the case was placed into “inactive” status in February 2016.

“At this time, there is insufficient evidence to support criminal charges in this investigation. Should new information be developed or a new victim come forward additional investigation will be completed,” Ratajczyk wrote.

Townsend, who now works for the Dakota County Attorney’s Office, did not respond to Sahan Journal’s request for comment. The Hennepin County Attorney’s Office declined to say why charges were not filed in 2015.

Alexis said she felt that Ratajczyk took her son’s case seriously.

“He believed us,” she said, recalling the day Ratajczyk called her to inform her that Hjermstad would not be charged. “He kept saying, ‘I don’t understand why. I believe there’s more.’”

Veteran Twin Cities attorneys say that sexual assault cases are difficult to prosecute when investigators only have one person’s word against another’s.

Joseph Daly, a professor emeritus at Mitchell Hamline School of Law, said that without another victim or other evidence such as photographs, prosecutors would likely decline to charge a case like Jazz’s.

Former Ramsey County Attorney Susan Gaertner, who now works as a private defense attorney, agreed with Daly. In her 16 years as head county prosecutor, Gaertner oversaw the prosecution of complex criminal cases, including sexual abuse and child abuse cases. She also previously worked as the Ramsey county attorney.

Gaertner said it’s challenging to charge criminal sexual conduct cases particularly when they involve children, because they’re often scared to report abuse and may feel ashamed.

“They can fear they won’t be believed, particularly when it’s a trusted figure in the community, such as a teacher,” she said.

Daly and Gaertner said it’s not easy for prosecutors to meet the legal threshold to file charges — proof beyond a reasonable doubt — regardless of the alleged crime.

“It’s hard to get a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt. That’s the reality, that’s our system,” Daly said. “We don’t put the burden on the defendant to prove himself innocent. We put the burden on the prosecutor to prove him guilty.”

Gaertner said “red flags” or suspicions, such as Hjermstad having boys sleep over at his home, are not sufficient to file charges.

“It’s not a crime to have young people over for sleepovers,” she said. “It’s certainly a red flag, but more so in an employment decision context than in a criminal context.”

Gaertner, who was not involved in Jazz’s case, added that prosecutors could have also been deterred from filing charges because the Minnesota Department of Education, which has a lower burden of proof than prosecutors, did not take action against Hjermstad.

The Minnesota Department of Education investigated Jazz’s allegation and concluded that there was “insufficient proof” to establish a preponderance of evidence that Hjermstad had abused Jazz, according to court documents.

The agency told Sahan Journal that under state law, it could not confirm or deny any investigation or determination of alleged maltreatment.

Young people’s allegations of sexual abuse, like Jazz’s, often aren’t believed when it’s their word against a respected educator or community figure, said Anderson, the St. Paul attorney representing many of Hjermstad’s victims and alleged victims.

“It’s the powerless versus the powerful, and they [authorities] defer to the powerful,” Anderson said.

Alexis pulled Jazz out of Excell Academy as soon as Grant told her about the abuse.

”It was a lot of different emotions and concerns about my child, how he was going to move forward in school, social[ly] and being athletic,” Alexis said.

Jazz began playing for a new basketball team.

“I don’t have to worry about anyone trying to touch me or anything,” he said in his Cornerhouse interview.

He told Sahan Journal it wasn’t a difficult transition to join a new basketball team. Still, he described feeling a “dysfunction” outside the structure of a school day.

“I always had something in my gut that somebody’s out to get me,” he said.

Jazz felt that authorities believed him when he first reported the abuse. But then the months and years passed. Nothing happened.

“As time went on, it was just like, ‘Well, this must be a normal thing,’” he said.

All he could do was focus on the sport he loved.

“If I’m just in my own thoughts, I can be stuck in one place,” Jazz said. “So I just kept going and doing what I needed to do, which was to play basketball.”

Did Hjermstad purposely prey on Black boys?

More than 90 percent of students at the schools Hjermstad taught at during his career, Excell Academy and the Mastery School — now Harvest Best Academy — are Black. Excell Academy is located in Brooklyn Park, a diverse suburb where nearly a quarter of residents are foreign-born. Harvest Best is located in north Minneapolis.

Alexis is certain that Hjermstad deliberately targeted Black youth like her son. Burke, whose office is representing about 10 of Hjermstad’s victims and alleged victims, said all of the survivors she represents or has personal knowledge of are Black, male and were minors at the time of the abuse.

Alexis felt like Hjermstad also stereotyped her, assuming that she was a poor single mom, when she was in a new committed relationship and living in a comfortable suburban home.

“I feel like he thought that I was this low-income, single Black woman who didn’t really pay attention or talk to my child,” she said. “He preyed on that.”

Eddie Grant, the school’s former equity director who Jazz had confided in, said that Hjermstad also targeted kids who were known for getting in trouble, or who had special education plans — kids who would be less likely to be believed.

Damion Davis, a Texas psychotherapist and founder of the Davis Counseling Center, a Dallas-based therapy practice where all clinicians and most clients are African American, said predators often find a vulnerability to exploit that will make victims harder to believe, like disability status, race or socioeconomic status.

There is an “automatic power differential” when a well-regarded white man in the community preys on Black boys, he said, adding that adults often devalue reports from children. Since Black children are often stereotyped as untrustworthy or troublemakers, he said, they “are believed at even lesser rates.”

In Davis’ counseling practice, he’s worked with many Black male survivors of sexual abuse. None of them mentioned that as a reason they sought out counseling; it came up months later, and he was often the first person they told.

“There’s a shame and embarrassment attached to it,” he said. “In some spaces, there’s still a very negative stereotype assessed to homosexuality.”

Men and boys may fear that others will stereotype them and believe that their sexual abuse means they’re gay, he said.

The African American community is diverse, but tends to lean a little more conservative on this issue because of a historically strong faith, which heightens the stigma for boys who report sexual abuse, he said.

On top of that, he said, there’s often a deep historic distrust in Black communities of institutions, due to decades of police brutality, medical experimentation, and exclusion from housing access. That makes reporting abuse even more difficult.

“There’s even colloquialisms in the Black community: You don’t call the police unless it is dire,” Davis said.

Hjermstad moves to another school

Excell Academy didn’t renew Hjermstad’s contract for the 2015-16 school year after Jazz came forward. But the school also did not make any disciplinary findings against him after conducting its own investigation into Jazz’s allegations, according to school records reviewed by Sahan Journal.

Hjermstad then applied to work at a different charter school, the Mastery School in north Minneapolis, which is now consolidated under Harvest Best Academy.

Alexis wondered why Hjermstad wasn’t fired. She was shocked to learn in 2020 that Hjermstad had moved to another school and abused more boys.

“They should have fired him with no pay, and I don’t understand why he was able to continue working at Harvest Best Academy with other children,” Alexis said.

Eddie Grant said he is still processing the news that Hjermstad abused more boys, many of whom he likely knew.

“If [Williams] handled that differently, is he able to go do all that other stuff?” he asked. “You can’t say for sure, but it definitely didn’t help.”

Anderson filed a civil lawsuit in July 2020 on behalf of a Mastery/Harvest Best student, accusing the school of negligent hiring. Court documents from the civil case show that Harvest Best did not call Hjermstad’s references when they hired him.

Hjermstad left a portion of his Harvest Best application blank, including a question asking why he left his previous position. He eventually said during his interview that he left due to “budget cuts.” Harvest Best did not call Excell Academy to verify why Hjermstad left, court documents show.

The Minnesota Supreme Court ruled in February that Harvest Best Academy may be liable for negligence when it hired Hjermstad. The case was sent back to lower courts, and is ongoing.

Harvest Best Academy said that it does not comment on pending litigation, but said that the district court had previously ruled that Hjermstad’s conduct was not foreseeable to Harvest Best, and that this ruling was not affected by the Supreme Court’s decision.

Schools are required to obtain professional training to investigate sexual assault allegations under Title IX, but they often don’t, said Billie-Jo Grant, the CEO of McGrath Training Solutions. Such investigations don’t try to determine whether criminal activity occurred.

“Their job is to determine: Did the employee commit a policy violation? Did they violate our policy? And is there a hostile environment present?” she said.

Charter schools tend to have less robust internal policies than traditional public school districts, Billie-Jo Grant said.

“The tricky part is, they’re creating their own policies, and they’re kind of having to reinvent the wheel,” she said. “I’ve seen some really lean handbooks.”

Some charter school associations provide guidance to help schools create policies, she said, but they often run behind on implementing the policies.

Schools should have policies in place governing appropriate boundaries between staff and students, she added. And if they are going to remove a teacher from employment, they should document why.

“The right thing is just to do a full investigation, to terminate somebody if you need to terminate, with the reason why,” said Billie-Jo Grant. “It should be reported to the certification agency and documented, so that they can remove that teacher’s license so they don’t get hired somewhere else.”

Ultimately, she said, schools typically do not face accountability for inadequate investigations unless a lawsuit is filed.

Until February 2025, when the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that Harvest Best might be liable for negligent hiring, Minnesota schools were considered immune from liability in these matters, which has fueled the problem, said Anderson.

“Administrators and officials have been taught — informed — that they’re untouchable under the law,” he said. “There’s a culture of permissiveness and insularity that the law gave them that just permeated the culture of education in Minnesota.”

Bailey, executive director of the Minnesota Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board, said that state law creates a gray area around reporting child abuse allegations. Schools are required to report to her agency when a teacher is terminated or resigns during an investigation, but the law does not explicitly state that they must notify the board when they don’t renew a teacher’s contract as a result of an investigation.

“Some school districts and charter schools interpret that mandatory reporting requirement to not include situations where they don’t renew a contract,” she said. “So some people use that as a loophole.”

Bailey said she’s spoken with legislators about clarifying this language to eliminate this gray area.

Bailey said she’s noticed an uptick in cases at charter schools where she has learned about sexual abuse criminal charges through the news, rather than a direct report from the school. Minnesota public school administrators are required to have a license with the state, which means they receive training in mandatory reporting. If public school administrators fail to report abuse, her agency can report them to the state Board of School Administrators, which maintains administrators’ licenses.

But charter school administrators are not required to be licensed by the Board of School Administrators, so the same process doesn’t apply to them if they fail to report abuse, Bailey said. That also means they may not have the same levels of training as their peers in traditional public schools, she added.

She’d like to see a law that allows the Minnesota Department of Education to withhold funding from schools that do not follow mandatory reporting requirements.

“We have protections in law for our special education students, which are incredibly important, and if there’s a failure to serve them appropriately, a district can lose funding,” Bailey said. “And so I think that you wonder, ‘At what point is the protection of children from predatory behavior also worth having a mechanism like that in place?’”

Hospitality House reinstates Hjermstad as a coach

Hospitality House, the faith-based nonprofit in north Minneapolis where Hjermstad volunteered as a basketball coach, placed Hjermstad on leave after Jazz reported the abuse allegations. Hospitality House conducted its own investigation into the allegations, but later reinstated Hjermstad, according to court documents.

After the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office declined charges in Jazz’s case, Hospitality House leadership recommended to its board that Hjermstad be reinstated as a basketball coach. At the time, Minnesota’s mandatory reporting law applied to schools like Excell Academy and Harvest Best, but not to youth organizations like Hospitality House; the Legislature closed that loophole in 2023.

“Aaron has coached for Hospitality House for more than 15 years. He has coached approximately 30 teams with over 100 different youth, with no known issues. Many of his co/assistant coaches have worked with him 15 years or more with no known issues,” reads the letter Hospitality House leaders sent to the board in 2016.

The letter was filed as evidence in the 2020 civil lawsuit Anderson filed against Hjermstad and Harvest Best.

“From the information we have, there does not appear to be any issues with him coaching, nor has there been any past issues,” the letter reads. “The police contacted several of his current, past players and families and based on this investigation the prosecuting attorney decided to decline charging. The police have returned all of Aaron’s belongings. Talking with his players and coaches we found no evidence of wrong doing [sic]. Further testimony of many players, coaches and parents, also support and want Aaron to coach.”

The scope of Hospitality House’s internal investigation is not clear. Jazz and Alexis said that Hospitality House never interviewed them as part of an investigation.

Hospitality House’s letter said that police were “vague” with Johnny Hunter Sr., Hospitality House’s executive director at the time, about what the allegations were, and that it was “difficult” to get more information.

“Aaron [Hjermstad] said neither the school nor the police gave him any further information,” the letter reads. “To date he has not been told what the accusation was. The police would refer to ‘alleged inappropriate activities.’ Discussions with coaches indicate it may be from a single student, but this was difficult to confirm.”

Hunter and George Rowley, the Hospitality House’s program director at the time, also wrote a letter addressed “to whom it may concern” supporting Hjermstad, which Hjermstad then sent to the Minnesota Department of Education in 2016. In their letter, Hunter and Rowley wrote that Hospitality House “fully supported” Hjermstad and “firmly believed” the allegations were unfounded.

The Minnesota Department of Education also investigated Hjermstad because of Jazz’s allegations, and ultimately closed the investigation without taking any action against him. According to court documents, the department said in a formal report that it recognized that some witnesses may have had information but declined to come forward “because of cultural taboos against homosexual contact in their culture.”

Hospitality House allowed Hjermstad to return with several conditions, and made him sign a document promising not to host any more sleepovers for Hospitality House children at his home.

Hospitality House’s current executive director, Charles Moses, did not respond to requests for comment. Rowley and Hunter also did not respond to requests for comment.

Hjermstad broke his promise. More boys would come forward years later, alleging that Hjermstad brought them to sleepovers at his home and abused them after supplying them with games and food just like he had done with Jazz.

“He just didn’t stop,” Alexis said.

Jazz’s case is revisited

Three boys who had been coached by Hjermstad at Harvest Best and Hospitality House came forward beginning in March 2020. One said Hjermstad offered him money to touch him inappropriately. Another awoke in the middle of the night to Hjermstad’s mouth on the boy’s genitals. The third reported that Hjermstad exposed himself in front of him and his teammates.

The boys, who were different from the other three boys Brooklyn Center police identified when Jazz came forward in 2015, reported that the abuse occurred between 2016 and 2020.

Brooklyn Center police called Alexis. Did she still want charges filed against Hjermstad for abusing her son, they asked.

Yes, she said, adding that he was still traumatized years later and couldn’t go to Timberwolves games. While she was grateful that charges were filed, she wondered what would have happened if Hjermstad had been charged sooner.

“We blew that whistle,” she said, “but nobody heard it.”

This time, the school and criminal justice system took action.

On March 5, 2020, Emily Peterson, the interim head of the Mastery School (now consolidated with Harvest Best), filed a police report upon receiving a complaint from a student. This was the first time school leadership had heard allegations of Hjermstad’s inappropriate behavior with minors, according to court documents.

Four days later, Hjermstad was fired.

“Mr. Hjermstad was terminated for insubordination after he refused to participate in an investigation interview regarding allegations against him,” Peterson, who is now director of Harvest Best Academy, told Sahan Journal.

The Hennepin County Attorney’s Office charged Hjermstad in 2020 for abusing Jazz and the three boys. He was charged with one count each of first-degree criminal sexual conduct, fifth-degree criminal sexual conduct and soliciting a child to engage in a sexual act; and two counts of second-degree criminal sexual conduct.

“When the 2015 case was reviewed again along with newer information in 2020 that was not previously known, the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office charged the case,” county attorney spokesperson Daniel Borgertpoepping said in a written statement. The office declined to comment further, citing ongoing criminal cases against Hjermstad.

For Jazz, the charges were overwhelming.

“It opened everything,” Alexis said. “Trauma on top of trauma on top of trauma.”

Around the same time, Jazz’s father died. The COVID-19 pandemic was also beginning to take over, forcing his schooling to move online. It all became too much for Jazz, then 17 and nearing the end of high school. News that Hjermstad was going to be charged prompted him to start reflecting about what had happened to him.

Jazz stopped playing basketball for his school.

“I didn’t want to be around it, and I just didn’t feel it anymore,” he said. “I like basketball, and I can play basketball, but I gotta get my body back right, because the way I’m feeling is yucky inside.”

The other three boys all spoke to interviewers at Cornerhouse about what they had experienced. Ratajczyk, the Brooklyn Center police detective who led the 2015 investigation into Jazz’s case, was assigned to investigate the new cases, and spoke with the boys’ mothers.

Hjermstad waived a jury trial and opted for a bench trial, which is when a judge reviews the evidence and issues a verdict. Hennepin County District Judge Martha Holton Dimick found Hjermstad guilty in 2021 of abusing Jazz and the three boys. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

Jazz heard about Hjermstad’s conviction, but thought he had been convicted for more recent crimes — not for hurting him. By then, the boy who loved basketball had become a shell of his former self, and was struggling with depression.

Around that time, Jazz was playing basketball with a friend one day and began to feel anxious. He needed to leave. His friend wanted to keep playing, so Jazz stole a car to get home, where he barricaded himself inside his room.

“I just felt like my whole process, what I was supposed to be here doing, changed,” Jazz said. “I don’t feel comfortable in my body.”

Months before his sentencing on Feb. 2, 2022, Hjermstad, who was out on bail, fled the state. He was pulled over on Nov. 30, 2021 by police in Idaho. Police searched his car, and found digital memory cards with numerous videos of him allegedly abusing boys, according to Anderson.

A list of about 200 boys’ names was also found in Hjermstad’s car; nearly 30 of them had notations that they had “slept in Aaron’s bed,” according to Idaho State Police Corporal Jared Shively, who pulled Hjermstad over and testified at a recent hearing in Hennepin County District Court.

Jill Oliveira, a spokesperson for the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, told Sahan Journal the agency is investigating the evidence collected from Hjermstad’s car.

“We have been able to positively identify 43 of the victims,” Oliveira said in an email statement. “Based on the evidence obtained during our investigation we believe that there were approximately 80 additional victims. Any additional information is part of the ongoing investigation.”

“That says something about how pervasive and how perilous and how long-standing this would have been,” Anderson said of the new evidence.

Anderson, who has represented victims of child sexual abuse in the Catholic church, said Hjermstad is one of the most “prolific” serial sexual abusers he has ever encountered.

“He’s a serious, serial predator that ranks among some of the worst we’ve seen,” Anderson said. “He persisted in it, and succeeded in accessing so many young and vulnerable kids of color in so many underprivileged communities for so long.”

The Hennepin County Attorney’s Office has not publicly commented on the number of Hjermstad’s potential victims, but a grand jury convened by the office indicted him in September 2024 with 12 more counts of first-degree criminal sexual conduct based on video evidence collected from his car in Idaho. The alleged abuse in those charges reportedly took place between 2013 and 2021. The office has not released details about the new cases.

Hjermstad’s attorney in the new cases filed a motion trying to exclude the evidence from his car, arguing that it was an unlawful search. Hennepin County District Judge Carolina Lamas denied that request. Hjermstad is scheduled to go to trial in September on the 12 new counts.

When Hjermstad was sentenced in 2022 for abusing Jazz and the three boys, one of the other boys’ mothers gave a victim impact statement, saying Hjermstad had hurt the community and underestimated her son’s strength.

“What you did to these young Black boys in the community, [my son] will never forgive you,” she said, according to court transcripts. “You thought we were so weak and that you thought you were not going to get into trouble.”

The complicated work of moving forward

This year marks a decade since Jazz first came forward.

Alexis wants to see the schools that employed Hjermstad, Excell Academy and Harvest Best, held accountable. Anderson is suing Harvest Best on behalf of a former student for hiring Hjermstad. It also faces a second lawsuit from Anderson on behalf of a former student for how it allegedly handled a sexual assault allegation against Abdul Wright, who taught at Harvest Best and was a Minnesota Teacher of the Year in 2016. Wright’s case is separate from Hjermstad’s cases.

“I think all the schools should be held liable for this, continuing to let this man work,” Alexis said.

Excell Academy has not been sued. Alexis said it’s up to her son if he wants to take action against the school one day. Burke said her law firm represents several former Excell Academy students, and has provided the school with two notices of claim, indicating possible future lawsuits.

Jazz and his mother still attend church at Mighty Fortress, which meets in Excell Academy’s gym — the same gym that Hjermstad coached in.

Jazz is 22 now, engaged, and will soon welcome his first child, a boy. Alexis hopes Jazz can teach his son how to play basketball one day.

He’s still processing how the abuse he suffered as an 11-year-old has reverberated through every part of his life. He’s haunted by an ongoing sense of wariness. He’s suspicious of people who approach him. He delivers food for DoorDash, a job that doesn’t require him to interact too much with strangers.

He knows there are no easy answers for how to move forward as a sexual assault survivor, but he’s doing his best to make a life for himself.

“It’s just still a lost feeling,” Jazz said of how he’s doing now. “I’m still trying to figure it out.”

Share your story: If you’ve been victimized by Aaron Hjermstad or know him and wish to share your story with Sahan Journal, please reach out to kpross@sahanjournal.com. Your name and information will stay confidential. Sahan will not publish any information without your consent.

Resources

If you or someone you know has been sexually abused, these local and national resources can help:

RAINN National Sexual Assault Helpline: 800-656-HOPE (4673)

The Sexual Violence Center Crisis Hotline operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, providing immediate and confidential counseling support to individuals in crisis: 612-871-5111

English (US) ·

English (US) ·